How I Pivoted from Mining Engineering to Product Management

TL;DR

I started in mining operations, then moved into product work by learning to code on the side and building internal tools. Over the years I worked across multiple industries as a bridge between operational problems and technology delivery, and I kept gravitating toward roles with more ownership and autonomy. Recently, I left my corporate role to build CareerDNALabs full time, combining product thinking with hands on engineering.

What connects every step is fit. I learned that doing well and being a good match are not the same thing. The best roles for me are the ones where I can bridge real operational problems and technology, with enough freedom to execute.

The Story

1) One-Sentence Theme: The title and theme that connects everything

If your career was a Netflix documentary, what would the title be?

If my career was a Netflix documentary, the title would be: "The Ops Guy Who Learned to Build."

The one-sentence theme is: I keep choosing roles where I can translate messy real-world work into a system, ship something useful, and own the outcome.

The label fits because I started in operational work where the job is to keep the system running, then slowly moved toward building the system itself.

In every chapter, the pattern is the same:

- I start close to real workflows and constraints (field operations, business teams, frontline pain points).

- I see where the system creates friction, especially where it forces people to do repetitive work or work around the process.

- I try to turn that mess into something clearer, usually by building a tool, a workflow, or a product change.

- Over time, I end up in roles with more ownership because I care about the end result, not just the task.

When the role becomes too routine or too controlled, I feel constrained, even if I can still deliver.

I am not the strongest coder in the room, and I am not trying to be. What I care about is using technology as a product to solve a real operational problem. That is why I call myself a Product Engineer.

2) Roots & Obsessions: Connecting early interests to current reality

Go back to the beginning. What did 10-year-old you want to be?

When I was 10, I wanted to be a game developer.

I loved playing video games, and I had access to a computer early. My parents gave me freedom to do anything with that computer, so I started tinkering with it. I was the kid who liked to click around, break things, fix things, and figure out how stuff works.

That early habit connects directly to what I do now. I am still the same person, just with higher stakes: take a messy system, understand how it works, then improve it by building something real.

My first corporate job as an Operational Surveyor in a Management Trainee program.

The unexpected part is that I did not start in tech. I graduated in Mining Engineering in 2015, right around the period when the energy industry took a downturn.

Even before my first job, I was the "tech wannabe" type. After high school I tried to get into computer science and failed the entrance tests three times. At that point, I went down the mining engineering path, partly because it was what my parents suggested as a practical option.

In my spare time I kept learning to code. My final project in university was about using technology to improve mining workflows and process efficiency, and I carried that habit into my first job.

That mix is what pulled me toward product and tech. Early on, I kept looking for ways to use software to make operational work simpler and more reliable. Over time, that turned into product work, and later more hands on building as well.

3) Moves & Decisions: The logic and friction behind every career move

Walk me year-by-year from your first job to today. Focus on the decision points.

This is the version that matters: the decision points and the logic behind each move.

- 2015: Graduated in Mining Engineering.

- Early 2017: Started my first corporate job as an Operational Surveyor in a Management Trainee program at a Testing, Inspection, and Certification company. The work was heavily driven by SOPs and strict routines. I learned a lot, but it was not a great fit because I work best with autonomy.

- During the field rotation: I had idle time between supervising daily operations, so I used it to learn coding fundamentals through ebooks and Udemy courses.

- End of year 1: Built an internal tool to improve a real process in the mining area. That project pulled me into work that connected field operations with head office systems. This was a pull. I liked seeing a tool change the workflow.

From the period when I started moving from operations into product work.

- 2018: Built a simple face recognition model project. It was not production grade work, but it helped me learn fundamentals and gave me a concrete artifact to explain in interviews.

- After moving closer to head office work: I was surrounded by full time engineers, and I did not feel confident trying to compete on pure coding. Instead, I leaned into product management. I became the person who could translate operational problems into clear requirements, then work with engineers and users until the tool actually worked in the field.

- Around 2021 to 2022: Left a stable role at a state owned company when the pandemic hit. From the outside, it looked like a safe job you could keep for decades. For me, it felt like I was getting too comfortable. This was both a push (comfort) and a pull (growth).

- Next chapter: Took a Product Owner role and was given a platform to build and maintain. That shift changed how I work. In a product role, the system does not matter if you cannot deliver.

- Over the following years: The same "ops first product" pattern kept repeating. I moved from mining into agile consulting, then food and beverage and hospitality, and later insurance. In each place I learned from operational experts, then helped ship tech that removed friction from their workflows. My scope grew from working mostly on my own, to leading small teams of 3 to 4, then teams closer to 10 to 15 people.

- September 2025 to now: Started building CareerDNALabs full time (CareerMeasure and CareerLore). This is the pure version of the thing I have been doing all along: own the problem, build the system, and ship.

The hardest friction behind the early moves was credibility. I did not have a computer science degree, and I kept having to prove I was not just interested in tech, but capable of delivering in it. That is why portfolios, case studies, and shipping small tools mattered so much early on.

4) Best Fit Reality: Which role felt most like you vs. fighting instincts

Looking back at that timeline, which specific role felt the most like YOU?

Looking back, the role that felt the most like me was my Product Owner role in agile consulting. I felt natural and energized because the expectations were outcome-driven. I had room to decide how to work, as long as I delivered. That trust made it easier to think clearly, take ownership, and ship consistently.

The contrast is my first role as an Operational Surveyor in a Management Trainee program. It was SOP-heavy and strict by design. Consistency, safety, and compliance matter in that kind of work, but the environment left little room to change the system. I could see problems and ideas for improvement, but making changes was slower and harder because the risk of disruption was high. Operational work is also the last thing people want to interrupt. Nobody wants an "improvement project" that risks slowing down the business or creating new audit questions.

Me around the coal mine during field work in 2017. This role felt like a bad fit because of the strict SOPs and lack of autonomy.

The difference was not the industry label. It was the work environment: autonomy, trust, and how much space there was to improve things without fighting the system.

I have also seen the same mismatch inside tech. A product role can still be a bad fit if the environment is controlled and micromanaged. Even when I delivered, constant monitoring and lack of trust drained my energy over time.

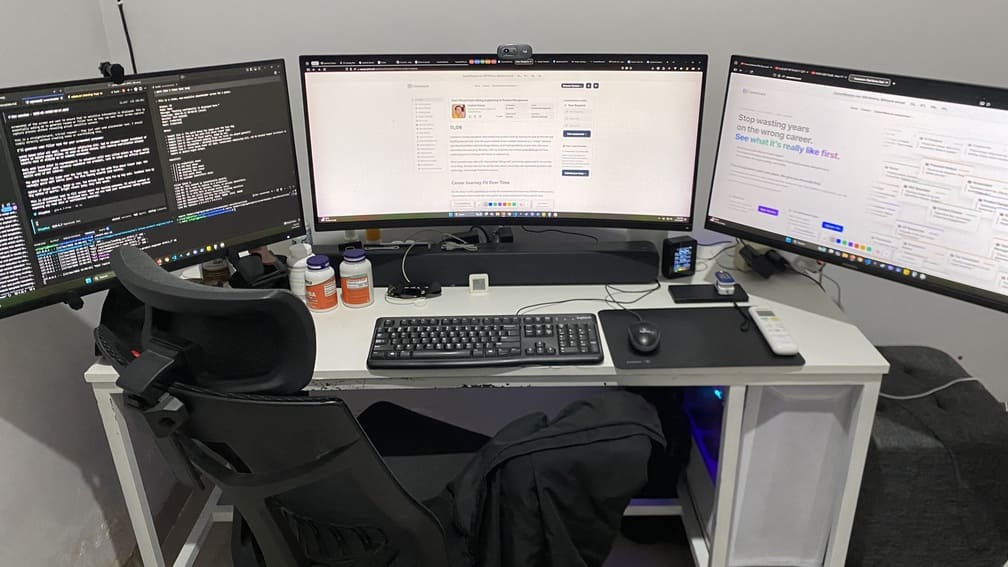

Career Journey Fit Over Time

For this story, I used CareerMeasure to take the assessment and import my LinkedIn career journey. CareerMeasure then scored each role against my results and turned it into a role fit chart.

I found the output surprisingly accurate. The role that felt most like me in real life also shows up as my strongest fit in the chart, specifically role 7, my Product Owner role in agile consulting. For me, fit means more than liking the job. It is the sense that I can show up as myself, do good work, and not feel like I am constantly fighting my own instincts.

At the same time, the chart helped me separate two things. Fit is about alignment. Delivery is about professionalism. I have still delivered in roles that were not the best fit for me, but it usually cost more energy and felt less sustainable over time.

CareerLore is where we publish the stories. CareerMeasure is the fit engine behind them. They are both part of CareerDNALabs, which I started building in September 2025. I'm still early in the journey, so I'm using stories like this to keep things grounded in real experience, not just theory.

If you want to try it for yourself, start with the free assessment.

5) Breakthrough Project: The specific case study that proved value

Tell me the story of the one specific project that defined your career or got you to the next level.

One project that shaped how I think about product work was an HRIS migration and improvement project I led later in a food and beverage company.

The problem: The legacy vendor HRIS had been under contract for several years, costing around USD 125k per year. During that time, the system was a constant source of friction. Users reported issues daily: server outages, downtime during peak hours, missing data, wrong calculations, and post-processing that still required manual data work. The workflows did not match how the business actually operated.

Each ticket was treated as a change request that took months to address and cost additional money on top of the annual fee. Even then, the fixes were superficial, not solving the root cause, just cheap workarounds. Despite years of complaints, no major decisions had been made to address the real problem.

When new management arrived, I joined as part of the team brought in to tackle these legacy issues. The HRIS was one of the first priorities because it touched every employee and every payroll cycle.

During my food and beverage industry chapter, working on the HRIS migration and improvement project.

The action: I started by talking to users across departments to understand what was actually broken and what they needed. I talked to the internal HR team to map their workflows and pain points. In parallel, I evaluated alternative vendors and explored what was possible within our budget.

Once I had a clear picture, I discussed opportunities with leadership and proposed a plan to management: migrate to a better SaaS tool that cost around USD 25k per year, and build internal tooling on top of their API to cover the gaps. The proposal was approved, and we signed the deal.

From there, I led the execution. We built the internal tools on top of the vendor API, tested and fixed issues as they came up, and shipped iteratively. When we launched, I socialized the new system to all employees, ran training sessions, and made sure the change management process was smooth enough for the transition to stick.

The result: We saved around USD 100k per year, and we got a system that matched the way the business actually worked. More importantly, it reinforced a pattern I keep returning to: a good product decision is not only about features. It is about fit with reality, and about owning the tradeoffs end to end.

6) Failure & Recovery: A time you felt unqualified and what you learned

Tell me about a specific time you felt totally unqualified or made a mistake.

I do not have a dramatic list of career failures, mostly because I try to count and calculate each risk before I move. I usually do not fight unless I am sure of winning.

But I do have one decision I count as a real failure: I left the best job I ever had in agile consulting for a much higher salary. Ironically, that move took me to the food and beverage company where I led the HRIS breakthrough project I just described.

The move was a pull, not a push. I did not leave because of a bad boss or burnout. I left because the offer was more than 50 percent higher, and on paper it looked like the rational upgrade.

A farewell moment in Semarang, before our retreat trip to Karimun Jawa. This was the best job I left for a higher salary.

The crisis was not immediate. The salary did make some parts of life better. The failure was what I traded away without realizing it. In that consulting role, the culture felt like "do your own thing" and "be your own boss" as long as you delivered outcomes. That environment fit how I operate. I had freedom, trust, and ownership.

After I left, I learned the hard way that you can upgrade one variable (money) and still downgrade the thing that actually matters (fit). When I do not have autonomy and room to own the outcome, I can still deliver, but it costs more energy and it does not feel sustainable.

The recovery was deciding to return to the version of work I keep gravitating toward: ownership and building. After my last corporate job, I took a career break and went back to building and scratching my own itch. That is what I am doing now with CareerDNALabs.

The lesson is simple: in my career, culture and autonomy are not "nice to have". They are the core of fit. I treat them like a requirement now, not a bonus.

7) Daily Energy Blocks: How a real day works beyond the 9-to-5

Walk me through a real day broken into energy blocks.

Right now I work from home and I am building CareerDNALabs full time, so the rhythm is simple but intense. Most weeks are a loop: pick the highest leverage tasks, ship something, then get feedback fast.

A real day usually looks like this, broken into energy blocks (the exact hours shift, but the pattern stays consistent):

- Morning (clarity and deep work): I start with a short to do list that answers one question: what will move us closer to a usable MVP this week. If I do not get this right, the rest of the day becomes noise. Once the target is clear, I do deep work on the most important build task.

- Afternoon (execution and iteration): This is where most building and testing happens. I build the product with AI support, covering both backend and frontend work. I do end to end testing myself and try to break flows the way a real user would. Then I tighten the UX, fix edge cases, and keep iterating until it feels usable.

- Evening (wrap-up, learning, distribution): I wrap up by collecting feedback and doing basic marketing and distribution work so there is a real feedback loop, not just building in isolation. If there is momentum, I keep going. If not, I switch to reading, research, or writing.

The intensity is real. Twelve-hour days are common right now, including some weekends. The stress feels lower than corporate stress because the work is aligned with what I enjoy, but it still takes discipline to avoid overthinking and to keep shipping.

If I had to summarize the current split, it is roughly:

- 80% building, testing, shipping, and fixing

- 20% marketing and distribution

After launch, I expect that balance to flip. I expect it to be closer to 70% marketing and distribution and 30% building, testing, shipping, and fixing.

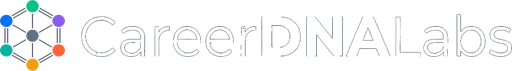

Late night debugging with the team was a normal occurrence in my previous corporate roles.

In my last corporate job as a Department Head for ERP in an insurance company, the shape was different. Engineers wrote most of the code, QA handled testing, business analysts did requirements, and internal users did acceptance testing. My time was split across meetings and alignment, research and improvement, and keeping delivery on track.

8) Tools & Systems: The essential gear, software, and frameworks

List the essential tools you use to do your job.

My stack is intentionally simple. I like the reactivity of modern frontends, but I do not want to overcomplicate things with heavy frameworks or build steps while I am still shipping an MVP.

I also built the product by working in English with AI coding tools. I did not start by hand-writing everything from scratch. The workflow is more like: describe what I want, generate code, test it end to end, then iterate until it works.

- Frontend: plain HTML + Alpine.js (no React or Vue). I want the UI to feel dynamic without the overhead of a bigger framework during early shipping.

- Backend: Python + Flask. Python was the first language I learned back in 2017 through the book Learn Python the Hard Way. It stuck because it is practical and fast to ship with.

My home workstation. Three monitors is overkill, but it works.

- Database: SQLite with WAL mode. I like the simple, lightweight approach and I want to see how far it can go before I need more complexity.

- Infrastructure: Linode VPS + Cloudflare (domain and CDN).

- Deployment: local dev, push to GitHub, then pull on the VPS for production.

- Documentation: docs as code in the repo so the project stays explainable and easier to maintain.

- AI tools: Codex is my main tool. I also use OpenCode and Claude Code, and I use ChatGPT web for discussion and thinking.

- Issue tracking: usually sticky notes or a markdown file. Heavy tools feel like overhead for me.

This is intentionally a mix of industry standard and going against the grain. Python and Flask are mainstream, and Cloudflare is common. Choosing Alpine.js and SQLite is more opinionated. For early stage shipping, I value systems that are easy to reason about and easy to deploy. Complexity comes later when it is earned by real usage.

9) Bad-Fit Traits: The personality type that would struggle here

Describe the personality type that would be miserable in your role.

The people who thrive as Product Engineers are the ones who do not just build things, but care deeply about what they are building and why. They like starting from a real problem, understanding the user, and then turning that into something tangible. They enjoy switching between thinking like a product person, thinking like a designer, and thinking like an engineer, even if they are not doing every role formally.

They also tend to think in systems. They care about the end to end flow, where users get stuck, what success looks like, and what should be measured. Technical details still matter, but the goal is not perfect code for its own sake. The goal is shipping something that works, is understandable, and helps someone in a real situation.

People who would be miserable in this role are usually the ones who prefer to focus purely on the code craft and stay far from users and product decisions.

Common bad-fit traits look like this:

- Needs rigid structure and fixed requirements before starting.

- Hates context switching between product thinking, UX, and engineering.

- Avoids messy feedback loops and prefers "closed scope" work.

- Wants to optimize architecture first, before validating whether the flow solves the real problem.

A task that often exposes this fast is user-facing iteration: sitting with messy feedback, making tradeoffs, adjusting the UX, and shipping another version without over-optimizing the architecture. If someone needs a stable ticket queue with little ambiguity, this kind of role will feel exhausting.

10) Learning & Advice: How you learn and what you'd tell your younger self

How do you actually learn?

The learning stack: I learn by building, then filling gaps with specific resources. Early on, I learned Python from Learn Python the Hard Way. I learned a lot from product and founder case studies as well, especially Starter Story by Pat Walls. For focus and output quality, Cal Newport's Deep Work shaped how I protect time and stay consistent. I also learned from mentors, including the "be capable, and be visible" rule that pushed me to treat communication as part of the job, not an extra.

Outside work, I have a street workout community I have been part of since 2015, after I graduated. Even though we do not train together as often now, we still keep in touch in a group chat. That kind of long running community gives you accountability and perspective, even when your daily life changes.

After a street workout session with my community in 2016. I'm at the bottom left, wearing orange shoes.

Advice to my younger self on Day 1: Start building immediately. Not only learning, but producing real artifacts. Build small projects, publish case studies, and practice explaining what you built and why it mattered. Do not wait for the perfect plan. Move, ship, and adjust as you learn. Shipping creates feedback, and feedback makes the next decision easier.

I would also tell myself to stop overthinking. Earlier in my career, I overanalyzed decisions and moved slower than I needed to. The more pragmatic approach is to make the best decision you can with what you know today, move first, and adjust as you learn.

If I could add one habit, it is protecting focused time. Deep work makes everything else easier.

Community Discussion

Share your experiences with this story

Delete Comment?

Are you sure you want to delete this comment? This action cannot be undone.

Leave a Comment